Gurley Lions Club serving the Gurley community since 1948

![]()

Gurley Lions Club serving the Gurley community since 1948

The source information for this article on Frank Gurley came from an article in the Civil War Times issued about 25 years ago and from an old 1920's publication called the Confederate Veteran, long out of print. The following dialog was taken from a 1920 issue of a magazine called the "Confederate Veteran"... This article was generously submitted by Bill Walker. Captain Frank B. Gurley feared for his life. He had no idea why he was so hated by the Yankees and insisted that he treated like an officer and prisoner of war. Northern newspapers had misrepresented the McCook incident and pictured Gurley as a criminal and murderer, and the Federals wanted their revenge. The Union officials want him to stand trial and assigned a heavy guard to prevent incensed soldiers and civilians to take matters in their own hands.

Capt. Frank B. Gurley, The Civil War - Part Two (Part One)

Capt. Frank Gurley finally arrived in Nashville by train and was placed in

a four foot by seven foot cell in the military prison and clamped in heavy chains. In the

same wing of the prison, there were 400 Federal prisoners all in ball and chain. Some

would whistle, some would sing, and all would curse and rattle their chains. Gurley said

"such a sight is better imagined than described."

Gurley was kept confined and his harsh treatment and illness made him delirious with

fever. He wrote to the Union commandant at Nashville, Major General Gordon Grainger, and

told him "long confinement and lack of attention will soon kill me and if that is

what you want, please do me the honor of having me shot as soon as your conscience will

permit." This complaint allowed him to go outside to the yard during the days.

By this time, Captain Hunter Brooke, who had been on the wagon with McCook, was acting

judge advocate of the Department of the Cumberland. He was most anxious to bring Gurley to

trial and convict him, and begin pressing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Judge

Advocate General Joseph Holt to arrange for an early trial of the "robber and

murderer". They agreed and arranged for an early trial before a military commission

to commence on December 2, 1863.

Judge Advocate Gen. Joseph Holt persisted in his efforts to have Gurley executed. |

Meanwhile, letters from Confederate Generals Nathan B. Forrest, Joseph E. Johnson, and William J. Hardee were received by the U. S. Army supporting Gurley's contention that he was a Confederate officer at the time of the killing and should be treated as a prisoner of War. These letters were sent to General U. S. Grant who advised the Confederate officers that the Gurley affair fell under the jurisdiction of Major General George H. Thomas and assured them Gurley would get a fair trial. |

A fair trial was impossible, considering the anger and prejudice against

Gurley. His lawyers, Jordan Stokes and Belie Peyton were able to present their evidence

and cross examine the prosecution witnesses. There seemed to be no question that Gurley

had shot McCook.

The case centered on whether or not he was an officer or citizen at the time of the

killing. The defense failed to produce a commission, perhaps because Gurley's house had

been burned to the ground by Union cavalry. Major General Lovell H. Rousseau did testify

that he had seen a commission earlier from Major General Kirby Smith authorizing Gurley to

raise a company of partisan rangers. The court also had a letter from General Nathan B.

Forrest that told that Gurley had served in his regiment from July 1861 and had not been

out of the service until his capture. In spite if this evidence, passions were too high

and Frank Gurley was found guilty of the murder of General McCook and sentenced to be

"hanged by the neck until dead".

Gurley commented that the prison was a horrible place with 800 Union prisoners and

"flies so thick you would get two of them in your mouth when you opened it". For

trying to escape, he was made to sleep in his cell in chains. Gurley saw one Yankee

prisoner slash his own throat with a razor. Eight of the ten men in the same lock-up with

Gurley were hanged.

Gurley's execution was delayed while the verdict and findings of the commission moved up

the chain of command. General Thomas approved the guilty verdict but suspended the

execution due to the unusual circumstances and battle excitement under which the crime was

committed. Thomas recommended the sentence be commuted to five years in prison and sent

these recommendations to the Judge Advocates office in Washington. Judge Advocate General

Joseph Holt seems to have been particularly vindictive in the Gurley case because he sent

the trial papers to President Lincoln with his recommendations that the original sentence

be carried out in spite of threats of retaliation from the Confederate Government. Lincoln

signed the papers approving the verdict, but he pigeon-holed the authorization to carry

out the sentence.

Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston wrote letters to Grant and Lincoln defending Capt. Gurley |

Gurley remained in prison for a year expecting to be hung at any time.

Then in January 1865, the army bureaucracy made a big mistake and Capt. Frank B. Gurley was included with other prisoners being transferred to Louisville for the exchange of Confederate officers who were being exchanged. Due to the high profile of Gurley's case, the jailer in Nashville asked for clarification from Washington, and was told by the War Department the order applied to "all officers" held in irons and close confinement. The jailer then sent Gurley to Louisville with eighteen other prisoners. |

From Louisville, the prisoners were sent to Pittsburgh then to Point Lookout, Maryland. In Pittsburgh, the group was nearly mobbed by a large angry crowd who had found out Gurley was in the group. They had thirty guards that protected them.

| On March 17, 1865, Capt. Gurley was exchanged at Aikens Landing, Virginia

and embarked on the long trek home. As he moved south, he found most of the railroads had

been destroyed. A year in prison had made him too weak to walk but some of the stronger

ones went ahead and sent back wagons and carriages for him. He arrived in Montgomery,

Alabama where he ran into his old commander General Roddy who gave him a horse. He

continued on to Madison County and stayed with his brothers and sisters in Gurley until

Lee surrendered. Frank Gurley went to Huntsville, took the oath of allegiance, and received the parole. He did not feel safe in Huntsville so he went to Gallatin, Tennessee for two months and "had a big time with the women". Then believing the danger had passed, he went back home and on November 6th, was elected sheriff of Madison County. |

Lt. General William J. Hardee |

Gurley did not know it but he was in greater peril than before because

General Joseph Holt found out Gurley had escaped punishment and got President Andrew

Johnson to approve orders to re-arrest Gurley and carry out the sentence. Orders went out

to all departmental commanders to search and capture the culprit. A sergeant was even sent

to the Louisiana swamps to search for him. No one thought to look for him at home until

news of his election to sheriff appeared in the papers.

On November 28th, Gurley was arrested, loaded with irons, and put in the Huntsville jail.

His execution was set for November 30th but a telegram arrived from President Johnson

suspending the execution until further orders. Frank Gurley's friends and neighbors had

come to his aid. They had arranged for a delegation to meet with the President and since

many of Gurley's supporters were pro-Union, Johnson was receptive to their case. About the

same time the Union Army commander in Huntsville had advised President Johnson the

citizens were threatening to resume killing Yankees if Gurley was executed. The situation

could turn real ugly. After the delegation returned from Washington, they began to prepare

a case, including a collection of character references and depositions from Confederate

soldiers who had been on that fatal raid.

The collection took a long time and Gurley remained in irons until one of his friends

wrote to General Thomas and pointed out the jail was escape proof. The irons were ordered

removed. In April 1866, President Johnson consulted with General Grant about the case, and

although General Holt still insisted that the sentence be carried out, Grant recommended

the case be dropped and Gurley be released upon taking an oath to remain a loyal citizen

to the United States. Gurley signed the oath and was finally released.

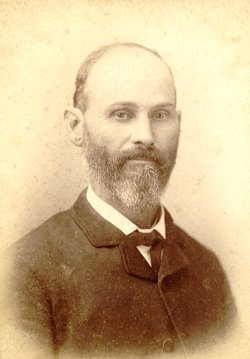

Frank Gurley in 1866 |

For the next fifty four years Frank B. Gurley lived on his farm near

the town of Gurley. Every year he held a reunion for the veterans of the 4th Alabama

Cavalry. He died on March 29, 1920, outliving, by many years, Captain Brooke, General

Holt, and others who sought his death during and after the Civil War. Long imprisonment took its toll on Capt. Gurley. Good food and proper care from his family, and Gurley neighbors brought him back to good health. This 1866 photo shows a thin and emaciated Frank Gurley soon after his release. |